It was hot, more than 95 degrees, and very humid. The city of Chicago beckoned, but it was too darn hot. Maybe tomorrow we’ll explore. Deb was below in the air conditioned cabin of La Tasse, our Island Packet 380. I assumed she was reading. She typically is. Earlier that day, we had taken our bikes along the harbor shoreline and up into Grant Park. But it was just too hot and humid to make a day of it.

But, hey, we were in Chicago, Monroe Harbor, at the Columbia Yacht Club dock. We were on a boat, our boat. We were fulfilling a dream. Not even the heat could change that.

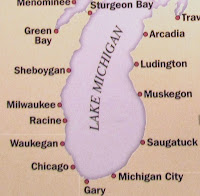

We’d been aboard La Tasse just over a month, having crossed Lake Michigan on June 17th from Manitowoc, our home port, to Ludington, Mi. The trip south with stops at White Lake and at seven of Michigan’s “beach harbors,” had gone smoothly. We’d seen lots of boats and tourists. St Joe and even Michigan City were pleasant surprises Not as I remembered them… I assumed we’d have more pleasant surprises as we headed north. At least I hoped we would.

But today, we were aboard our boat and in Chicago, one of the world’s great waterfront cities. Today was a day for thinking, for daydreaming….

I looked out over the harbor and at Chicago’s skyscrapers and thought about the millions of people who now live and work in the region. One hundred and seventy five years ago, a nano second in historical perspective, this place was hardly a village. Southern Lake Michigan, and particularly this southwestern end, had become a world class population center in a relatively short time. Why did that happen, I wondered? Certainly there were other lake port possibilities. Why here? Was it the Chicago River, Lake Michigan, or the people who came here? Or, was it just fate?

It’s why we do this, I thought. It’s why we cruise. Most of the people who visit or even live in this city, don’t know why it’s here; don’t understand its history. Sadly, that’s true for the entire Great Lakes region. Too few really appreciate the varied roles played by these great lak

es. Cruising allows us to retrace the steps of those who used these Great Lakes first, the Native Americans. We can retrace their steps and understand better how they were eventually pushed away by the immigrant Europeans who then largely built, for better or worse, what’s here today. For us, cruising filters out the crush of commerce. It helps us think seriously about the successes and the mistakes; about what we must now do to protect and preserve the true essence of life in this still beautiful spot on earth.

Yes, today was a day for thinking, for daydreaming…

Michigan’s Riviera

The 55 nautical mile (nm) trip across Lake Michigan on June 17th started uneventfully. Early morning haze, the weather forecaster said, would be followed by clearing skies and a light northwesterly breeze. Perfect for the west to east trip, I thought! Two hours into the crossing, about 13 miles out, we were encased in fog, thick fog. We’ve not had a lot of experience with fog so the conditions were a bit unsettling. We used the radar screen almost exclusively, switching back every 15 minutes or so to check our course. We were traveling along the ferry route. I’d previously calculated that we’d meet the 410' Badger at mid-lake, at about 10 am. Finally, she appeared on our radar screen, about 5 nm off the port bow. Traveling at 12 knots and adding our 6, she’d be abeam in about 20 minutes. That was less time than I had hoped for. I hailed the vessel and, thankfully, got an immediate response from the helmsman. “We’ve been following you on our radar for the last half hour,” he said. We agreed to stay out of each other’s way! Still unseen, she blew her horn as she passed to port, about a mile away.

An hour later, the skies began to clear, the sun burned off the fog and the promised northwesterly breeze arrived. Life was good again.

We docked in Ludington about 4:30 local time. The trip across had taken the now predictable 8 ½ hours dock to dock. We showered, enjoyed a bottle of champagne and then went to dinner. The bubbly wasn't only meant to christen our journey; we were also celebrating our 39th wedding anniversary.

The trip south from Ludington to New Buffalo would be “busy.” These are after all Michigan’s beach harbors, Michigan’s Riviera! In the late 1980s we’d visited several of these ports aboard All That Jazz, an O’Day 34 owned by friends from Cincinnati. We knew what to expect. Tourists flock to these beautiful harbors from all over the Midwest. As well they should. Lake Michigan’s waters are warmer here than in the north. And, with few exceptions the river harbors and inland lakes offer some protection when Lake Michigan kicks up her heels.

The Early Days

Madeline La Framboise was one of them. She was born in February 1781 on Mackinac Island after her parents were removed from the area of St Joseph, MI by the British (They “won” the French and Indian War, you recall. It ended in 1763). Her father was a French fur trader who had worked the west coast of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula in the mid-1700s. La Framboise was raised in an Ojibwa village at the mouth of the Grand River, near present day Grand Haven. She married Joseph La Framboise, a French fur trader, in 1794. Together they owned and operated a number of trading posts in western Michigan. When her husband was murdered in 1806, she carried on alone earning $5,000-$10,000 a year at a time when $1,000 was considered a handsome sum for an experienced fur trader. Eventually though, she caved to John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company, sold her business in 1818 and returned to a stately home on Mackinac Island. She dedicated the remainder of her life to education establishing the first school for Native American children on Mackinac Island. Madeline La Framboise eventually donated the property next to her home for the present day site of St Anne’s Church. Appropriately, Madeline is buried beneath the altar.

When fur trading ended along this coast, the lumber barons took over. But not, of course, until they evicted the Native Americans, including the heirs of Madeline La Framboise. The 1821 Treaty of Chicago took care of that little detail. That treaty, completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 and transportation provided by the Great Lakes schooner cleared the way for European immigrant settlers to populate the area. Michigan became a state in 1837, some twenty years after Indiana her neighbor to the south.

William Montague Ferry was one of the earliest permanent residents along this coast. He was an east coast educated Presbyterian minister with “operations” on Mackinac Island. In 1834, he and a traveling companion transited Michigan’s Lower Peninsula from Detroit following the Grand River to its Lake Michigan terminus where he platted a town (now Grand Haven). I suspect he even stopped at a fur trading post or two along the way; posts that had been established years earlier by Madeline la Framboise and her husband. Ferry returned to the area with his family and sixteen other homesteaders in November 1834 aboard the schooner Supply becoming Grand Haven’s first permanent residents. The western Michigan cities of Ferrysburg, Ferry, Whitehall and Montague are all named for him or members of his family. Ferry died in 1867 a very wealthy man. It wasn’t the Sunday collections or his sermons that made him rich. Lumber was his game.

The lumber era along this coast (roughly 1850-1900) brought major changes to the landscape. Saw mills lined the shorelines of the lakes and rivers adjacent to Lake Michigan. All winter long, the loggers worked to harvest Michigan’s virgin white pine. Some towered 200 feet in the air and had trunk diameters of 6-8’! From 1870-1880, Michigan led the nation in lumber production. For a couple of decades, the forests of the Great Lakes accounted for more than one-third of the lumber produced in the nation. Sustainability was a foreign concept. If anyone was thinking about resource management, it wasn’t obvious in the result. Thousands of acres were reduced to stumps and piles of brush. The discarded branches dried and became fuel for the fires that raged during those years. The Peshtigo, WI (about 60 miles northeast of Green Bay) fire killed 1,200 people and burned 1 million acres on the same October 1891 day that Chicago burned. The Peshtigo fire remains the greatest fire tragedy in U.S. history.

That same day another fire broke out along the western shore of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula destroying the coastal towns of Holland and Manistee. That fire didn’t stop until it reached Lake Huron, about 150 miles to the east! Two hundred Michiganders lost their lives in that fire. Another 15,000 lost their homes.

Lumbering continued along this coast until the trees were gone. By 1900, forty million acres in Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin had been stripped clean.

Farmers, generally speaking, were brought in to clean up the mess.

The Harbor towns

We visited ten ports along Michigan's southwestern coast on this trip. All were on navigable rivers or lakes adjacent to Lake Michigan. No artificial man made harbors here! The wide beaches and nearby dunes are covered with soft, white sand. The lake breezes cool the air. And, the harbors face mostly west providing incredible sunsets over the expanse of Lake Michigan. And no, I’m not being paid by the Michigan Chamber of Commerce and Tourism!

We didn’t really notice the tourists or the pleasure boaters until we reached Grand Haven. White Lake was laid back, even remote. Muskegon was more crowded, particularly along the beach, but we were at a marina some miles from either town or the beach. That wasn’t the case in Grand Haven. When we arrived on June 26th, a warm sunny Sunday, there were boats and boaters everywhere. The shoreline was crowded with tourists, most were watching the boats. We smiled and waved keeping a watchful eye on our new and floating“neighbors.”

Cities everywhere seek to attract and entertain tourists. For some, like Munising, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, it’s a simple matter of using what God provides. In their case, it’s the Pictured Rocks coastline. Niagra Falls might be another example. But, for most, it takes a little creativity and lots of work. There are events to plan, finance and promote. Roads, hotels and restaurants must be built and staffed. Most then look to create something unique, something that will make them special and remembered.

One of the more unusual efforts is to be found in Grand Haven, MI. The Grand Haven Musical Fountain is located on the north shore of Grand River and directly across from the city marina and downtown. Each day at dusk from Memorial Day to Labor Day, viewers are treated to a roughly half-hour show featuring an incredible display of synchronized music, water and colored lights. Every show is different. The thing is huge! Built by volunteers in 1962 at a cost of $250,000, it was then the largest musical fountain in the world. Fifty years later, its original nozzles and pumps remain intact. Its 200 lights in five different colors accent a water spray that’s 240’ wide and 125’ high. I’m not entirely convinced that the Musical Fountain is the foundation for the tourist trade in Grand Haven but I am sure that most people enjoy it. We sure did!

Up the lake a bit (yes, when upbound on Lake Michigan you’re headed south. But then, once again, I digress….), Saugatuck took an entirely different approach. In the 1880s after the lumber men were finished, the port began a natural transition to tourism. In 1910, a group of Chicago artists established a Summer School of Painting and a huge dance and concert hall was built on the water front. Big Pavilion was a popular Lake Michigan destination until it burned in 1960. Those flames, however, did not destroy the seeds planted in the 1900s. Today, the area reins as “Michigan’s Art coast” and has an affiliation with the Art Institute of Chicago. Rounding out its uniqueness, it’s a popular destination for the gay community as well. Deb explained that when I asked about the rainbow burgees in the marina. I’m forever grateful for her insight.

The roughly 2nm trip up the Kalamazoo River to Saugatuck and Douglas is one of the most beautiful on the Great Lakes, particularly when its quiet and not congested. Finding such conditions is, however, the hard part.

We happened to be in the harbor over the July 4th holiday. The streets and shops of Saugatuck were crowded. The restaurants were packed. We made the right call by docking at Tower Marine in Douglas, across Kalamazoo Lake.

Holland and Saugatuck provided a rare opportunity for us to share our cruising adventures with family. Sister Julie and brother-in-law Lee Zebro have sailed with us for a portion of the summer for years. We were glad to have them aboard again this year. Seldom though, are we able to share these special times with our sons and their wives. This year, son Andrew, wife Emily and pooch Boomer joined us July 1-4. What fun. After finally docking at Tower Marine on July 2 (Yes, we went aground in the marina fairway. We only draw 4' 7" for goodness sake. Boomer learned a few new words that morning.), we lowered Stanley from her davits. That inflatable got the work-out of her life. If you press hard enough, Andrew might even tell you that he learned something about shear pins! Sleeping six and a dog aboard LaTasse was crowded but very workable. Thanks, Andrew and Emily, for making the long drive from Columbus.

The roughly 40nm stretch from Saugatuck to New Buffalo was familiar. We first visited these ports with our Cincinnati friends Barb and Bob Sammis in the early 1990s. The Sammis’ introduced us to life aboard a sailboat; more on them later.

The Lake starts to narrow along this part of the coast as one heads south, southwest. Winds from the north or northwest can create ocean-like rollers in this area. They’ve had 250nm of open water to do their thing!

The big positive surprise on this leg was our time in St Joe. Earlier trips to that harbor were not particularly memorable. I even considered bypassing St Joe this time. But, the crew prevailed and it’s good they did. East of the railroad bridge at the harbor entrance, most of the river is barely navigable by anything but shoal draft power boats. We stopped short of the bridge and headed into West Basin. What a find. The basin is home to the St Joe River Yacht Club and its wonderful restaurant; the people at the marina are friendly and helpful. The marina staff even provides rides to and from St Joe so visiting their tourist friendly downtown was not a problem.

St Joe has its own special connection with early French explorers. Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de LaSalle claims to have discovered the river mouth in about 1669. His men built a stockade and used it as their base for the early explorations of Indiana, Illinois and the Mississippi River. LaSalle is, of course, credited with claiming the mouth of the Mississippi for France in 1682. He also built Le Griffon, the first full-sized sailing vessel on the Great Lakes (she was 30-40’ long and displaced 45 tons). They sailed Le Griffon up Lakes Erie and Huron to Mackinac and then Green Bay in 1679. Loaded with furs, but sans LaSalle, she was lost on the return voyage.

For a time in the early 1830s, St. Joe rivaled Chicago for predominance on southern Lake Michigan. In 1826, she was the first city on Lake Michigan to receive Federal funds to improve her harbor access. Chicago, the second city to receive such badly needed money and technical support, would wait another seven years for its first installment. St Joe and her western rival Chicago would also receive Lake Michigan’s first lighthouses in 1832. Both cities, of course, were destined to flourish during the “golden age of sail” on Lake Michigan, roughly 1835-1880. But, like the Energizer bunny, Chicago just kept going. By 1871, the year of the Chicago fire, Chicago welcomed more ships than New York, San Francisco, Philadelpha, Baltimore, Charleston and Mobile combined! She was one of the greatest ports in the world. St. Joe became an afterthought.

And it wasn’t just the heat. On the Great Lakes, summer heat is often accompanied by rain, strong thunderstorms, strong and gusty winds and, at times, tornados. Nasty, mid-morning thunderstorms were forecast for New Buffalo on July 11. The morning radar confirmed a strong band of storms southwest of Chicago and heading northeast. Local police in New Buffalo walked the docks that morning warning boaters of the forecast. We secured things, double checked the dock lines and headed into town to do some grocery shopping. We were barely inside the store when a good, old fashioned thunderstorm broke loose. It rained. It blew hard. Lightning split the sky. Then, the lights went out. I mean all the lights. The town was dark! Store management gave us a choice; leave the store or head to the basement. Obviously, with no place else to go, we went to the basement. Thirty minutes later it was all over. No harm done. I’ve spent lots of time in grocery store “back rooms.” As “back rooms” go, that one wasn’t bad.

Such storms aren’t all that unusual, of course. But when they come across 40-60 miles of open water, they are impressive and sometimes dangerous. Why some boaters tempt fate by knowingly going out when such conditions are forecast, I’ll never understand. Getting caught is one thing. Not respecting these lakes is quite another. It’s “pleasure boating” Deb constantly reminds me.

Like so many ports on this coast, New Buffalo’s harbor is created by a river, the Galien River in this case. This beautiful sliver of water meanders for miles north and east of the city. What a great place for a dinghy trip. Within minutes, the tourists and traffic are replaced by waterfowl, deer and dragon flies. Remote trips like this have always been favorites of ours. Over the years Deb and I have explored dozens of rivers with our inflatable. But, truth be known, I’m a bit of a wuss. What if the motor stops when you’re 5 miles upriver? Some would say there’s a bit too much of my father Hubert in my blood. I suspect my own apprehensions about such things help explain my admiration for the true explorers. Each, in their own way, have the courage to explore uncharted regions without a knot in their stomach. At least it seems so…

Breaking Away

Spending those days in New Buffalo created a flood of very good memories for me. My first experience on a sailboat was in that harbor. I will never forget that first time behind the wheel with all sail set. It happened just outside the New Buffalo breakwall. It was 1989. I’ve told the story dozens of times. Once more can’t hurt.

Deb and I are farm kids. We both grew up on dairy farms in Wisconsin. Neither family had a boat, not even a row boat for fishing. We learned to swim, of course. At least I did. Deb was given the opportunity to learn but when the instructor literally “threw her in the lake,” she vowed no more. Boats and water were not really part of our early years.

We met Barb and Bob Sammis shortly after moving to Cincinnati in the summer of 1981. Bob’s family owned a business that made and sold life preservers, among other things. In 1987, they fulfilled a dream. They bought a 34’ O’Day sloop, named her All That Jazz and put her in a slip in the New Buffalo harbor. We were invited to join them for a weekend aboard the boat that next summer. We found a way to politely decline. Thankfully, they persisted and asked us again the next summer. I recall telling Deb at the time that we should go. Barb and Bob were, after all, good friends. How bad could this be? We could just “suck it up” for a weekend.

Suck it up, we did!

That next summer we were aboard Breakaway, our very own 1984 Catalina 27. Brookville Lake (Indiana) proved to be a great place to learn. The reservoir is about 15 miles long, split roughly in half by a fixed bridge with about 10’ of vertical clearance. The lake is, at most, a half mile wide. The winds are fickle. We tacked often as we sailed to the bridge and back more than 100 times over the next eight seasons. We’ve never looked back.

Sailing changed our lives and gave us a much more complete marriage. It gave us both an escape from the pressures of building careers and raising a family. It gave us a retirement dream we could share, a loving respect for Mother Nature and an insatiable appetite for America’s Great Lakes.

To the surprise of many of our friends, we moved north, to the Wisconsin coast and the Great Lakes, when I retired in 2008. We bought La Tasse and began spending summers aboard, exploring and learning.

Thank you, Barb and Bob Sammis.

Lake Michigan’s South Shore

Julie and Lee left us in New Buffalo, taking the train back to Milwaukee via Chicago. We were on our own again. As much as we enjoy the company, we do savor our time together; just the two of us and LaTasse. We began to look forward to Chicago and ports north. But first, we set out to explore Michigan City, IN.

It’s a short 8nm from New Buffalo to Michigan City, IN, SSW. July 13th was a mostly sunny day with a light northerly breeze. Waves on the lake were 3-5’, reflecting the fact that the wind had been blowing from the north for two days. After clearing the roughed up waters just off the New Buffalo breakwall, we hoisted the jib and motor-sailed making good time with a following sea.

In 1818, the Hercules wrecked with all hands lost along this portion of the coast. It’s an unusual story. Hercules, an Army supply ship, was the first decked vessel to operate on a regular basis west of the Straits of Mackinac. She left Chicago on October 2, 1818 carrying a cargo of whiskey (less bulk than the grain, I guess!) and headed for Detroit. She floundered in a storm. The bodies of her crew of five and one passenger, a Lt. William S. Eveleth, washed ashore near here and were buried by the Native Americans who, presumably, also found and claimed some of the cargo. That part of the story is well documented. Less well known, for the next twenty years, John Farmer, the Detroit-based cartographer, included a notation on his maps of southwestern Michigan marking “Lieut. Evileth’s (sic) Grave.” To this day, no one is quite sure why he did that.

The feel of this trip changed for me as we headed into the Michigan City channel and Trail Creek. Despite her “play land” sand dunes, Michigan City is at the eastern end of the industrial head of Lake Michigan. The smokestacks of Gary and Burns International Harbor were visible even in the haze. That industrial feel would continue for the next two weeks, until we were north of Milwaukee, WI.

Chicago

We love Chicago. For many it’s America’s only livable big city. Her downtown harbors extend for 8nm from Burnham Harbor on the south to Montrose on the north. No other large city on the Great Lakes affords boaters with such easy access to the center-city. Chicago may not be cheap, we paid $3 per foot, but she is easy!

We left Michigan City, IN at 7:30 am on Sunday July 17th. The sun was shining, it was in the low 70s and the wind was SSW about 10 knots. The 35nm trip would take us about six hours. We had hoped for a clear day as Chicago’s skyline is visible from Michigan City on most days. But, that was not to be. As the temperature and humidity rose, the haze thickened. We didn’t see Chicago’s skyline until we were just 7nm out.

Monroe Harbor was busy. Lots of boaters were taking advantage of the warm mid-summer day. Besides, they had just gotten their harbor “back.” The Chicago to Mackinac sailboat race was underway, starting from this harbor as it has since 1898. In 2011, 361 boats started the 290nm race just days before we arrived. Tragically, and for the first time ever, the race suffered weather-induced deaths. Two sailors from Saginaw, MI were lost when their boat, WingNuts, capsized in a nighttime thunderstorm on July 18. Thankfully, six crew members were rescued by a competing boat. A subsequent review of the incident by U.S. Sailing concluded that the boat’s unconventional design made it “unsuitable for sailing in an offshore distance race on Lake Michigan.” It was another reminder that these are, in fact, Inland Seas; that ship wrecks and death on the water aren’t just history.

Chicago was all around us; The Columbia Yacht Club (CYC), Lake Shore Drive, Grant Park, the Buckingham Fountain and, of course the skyscrapers. We took a spot along the pier at the CYC.

The CYC clubhouse is actually a retired ferry. The MV Abegweit was first launched in 1946 in Quebec, Canada. She’s 372 feet long and displaces 7,000 tons. In her “hay day,” she carried as many as 950 passengers and 60 cars (or 16 railcars) across the Northumberland Strait (in the mouth of the St Lawrence River) between Port Borden on Prince Edward Island and Cape Tormentine, New Brunswick. While ferries still operate in the Strait, a roughly 6 ½ nm bridge, which opened in 1997, has significantly reduced the need for water transport in the area. The MV Abegweit, or MV Abby for the purists among you, has been at CYC since 1983. Unlike Deb and me, she at least moved south to retire.

For her size, Chicago is a “young” city. Her recorded history dates to the late 17th century with the arrival of the French explorers, fur traders and missionaries. But the city wasn’t “founded” until the 1830s, long after Cincinnati had become America’s first major inland city.

The early attention was on the Chicago River and the relatively short overland portage to the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers. But Indian unrest in the area had discouraged the Europeans from settling there for forty years. Fort Dearborn wasn’t built on the Chicago River until 1803, for example. Then, it was destroyed by the British in the War of 1812 and not rebuilt until 1818. The Treaty of 1831 and subsequent skirmish with Black Hawk in 1833 basically took care of the Native Americans. The town of Chicago was incorporated on August 12, 1833. The population totaled 350 souls. Cincinnati’s population, by contrast, was about 30,000 in 1833.

The Illinois and Michigan Canal

The short portage to the Mississippi created an opportunity for commerce; a way to get products, particularly lumber, from the Midwest to America’s wood-starved but fast developing Plain states. Wheat rounded out the return trip. Recall that the Erie Canal began operations in 1825 allowing relatively easy water transport to and from the Great Lakes and America’s east coast. The potential at Chicago was clear to most. Still, the city languished until a grant from the Federal Government in 1833, allowed development of an improved harbor entrance to the Chicago River. Over the next seven years over $100,000 would be invested in that project by tax payers in the east. In 1836, with the harbor issue settled, construction on the 96 mile Illinois and Michigan canal from Bridgeport to La Salle commenced. It would cost over $6 million and claim an unknown number of Irish immigrant lives. It wouldn’t be completed until 1848. By then, the railroads were making canal transport largely irrelevant.

That canal, and its sister, the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, sparked a controversy that continues even today.

Chicago grew rapidly after the fire of 1871. Much of the development occurred along the Chicago River as it was an easy way to dispose of the human, animal and industrial waste generated by an ever concentrating population. By 1885, the Chicago River was a nasty sewer. That wasn't really a problem since the waste was carried away into the harbor and eventually the vast expanse of Lake Michigan. Oops, the good citizens eventually realized, that’s where our drinking water comes from. (Still does, by the way.) Not a problem said these ingenious people; we’ll just change the river’s direction of flow. We’ll cause the water to flow from Lake Michigan and to the Illinois and Mississippi River taking with it Chicago’s waste. By 1892, the job was done. They fooled Mother Nature. And, that’s not nice.

The canal has had its unintended consequences. It now provides invasive species, like the Asian Carp, direct access to the Great Lakes from the Gulf of Mexico. The Army Corps of Engineers has recently erected electrified barriers to keep the carp from entering Lake Michigan. The fear is that they will destroy the now lucrative recreational fishing industry on the Great Lakes. Tragically, the zebra mussel, another invasive species brought to the Lakes years ago by ocean freighters transiting the Welland Canal, may already have that job well in hand. The little critters, billions of them, have helped to clarify the Great Lakes waters but they’re also adding to the already burdensome phosphorus load in the Lakes and depleting the micro-biological food supply that is needed to support the fingerlings and other small fish. Without small fish, there can’t be large fish.

The phosphorus problem is well recognized but largely ignored. The Wisconsin legislature recently passed a bill that restricted the use of phosphorus for some purposes. Farmers, the largest single user of phosphorus, were exempted. Worse yet, the 2011 Legislature then gutted the portion of the bill that would have required modernization of community sewage systems. Yes, we still knowingly tolerate the discharge of sewage and industrial waste into our Lakes and streams. We spend billions on political campaigns but can’t find the money to upgrade our badly worn and outdated municipal sewage and water treatment facilities. In many ways, we’re worse than the early Chicagoans. We should know better. We should learn from history.

The SS Eastland

The Chicago River architectural tour is a “must do.” We’ve been to and through Chicago many times over the past forty years and never paid much attention to the design or history of the downtown buildings. On this trip, joined by our dear friends Cindy and Paul Blasé (St Louis) and Karen and Larry Turner (Austin, TX), we took the roughly three hour tour and thoroughly enjoyed ourselves. The tour guides were great, provided wonderful historical perspective and helped us see the skyscrapers as never before. Along the way, between Clark and La Salle Street and on the south bank, the tour guide casually pointed to a marker on shore. I doubt many on the tour boat even paid attention. Fewer still, I suspect, realized that they were passing the site of the largest loss of life disaster on the Great Lakes, ever!

The SS Eastland was commissioned in 1902 by the Michigan Steamship company and launched as a passenger ship in 1903. She was big, 265’ long and almost 2,000 tons gross weight. She carried over 2,500 passengers on her many trips.

From the beginning, the Eastland was prone to listing. She was top heavy; her center of gravity was too high.

On July 24, 1915, the Eastland and two other passenger steamers were in Chicago, chartered to take employees of the Western Electric Company to a picnic in Michigan City, IN. Passengers began boarding the Eastland about 6:30 am. By 7:10 am the ship reached her capacity of 2,572. It promised to be a beautiful summer day. Accounts vary but at approximately 7:30 am, passengers on the upper deck rushed to the port side, perhaps to get a better view of the city. The Eastland lurched sharply to port and then rolled completely on her side. Eight hundred and forty four died that day. Many were women and children.

No one was ever found guilty of a crime in that disaster. Accidents happen I guess. Not!

Headed North

We left Chicago’s Monroe harbor on Saturday morning July 23. On the way, we passed the Chicago light. That majestic light has been at this location since 1919. Originally constructed for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, she featured, for nearly century, a stunning Third Order Fresnel lens that was meant for the lighthouse at Point Loma, California. The Chicago light was automated in 1979. The lens was eventually removed and is now “home” and on display at Cabrillo National Monument at Point Loma. (Cabrillo, a Portuguese explorer, landed at San Diego Bay in September 1542. Tell me more about how the east coast British colonies “built” America.)

Our trip that overcast morning was a short 6nm north to Belmont Harbor. We were going to a Cubs game, to Wrigley Field! The ballpark, according to our cruising guide, was a “leisurely 15-minute stroll down Addison.” Yah, right! First, you’ve got to get from the harbor and across busy Lake Shore Drive, a task complicated on that morning because the pedestrian underpass was closed due to flooding. It had rained 6 ½ inches at O’Hare overnight. We took a cab to Wrigley field. The Cubs beat the Astros 5-3. It was one of just 71 wins for the Cubs in 2011. In thier Division, only the Astros were worse.

Belmont Harbor was a disappointment. The docks, harbor entrance and fairways were fine. The boathouse facilities were terrible and a very long way from the docks. Lake Shore Drive effectively isolates boaters from everything in the area unless you have a car. It’s not a place for transient boaters. Not at $3 per foot.

Our return trip to Waukegan, IL began on July 25th. That day helps make my point about the unpredictably of the weather, particularly the wind. The day started peaceful enough. The sky was overcast with a light breeze out of the NW. The barometer at 30.03 had not changed materially in two days. The forecast had called for mostly overcast conditions and a 10 knot breeze from the NE with late-day clearing skies. Shortly after leaving the harbor, the wind piped up to about 18 knots from the N. We were headed NNW. Waves on the lake were 4’-6’ and confused. I took the helm and bore off to the NNE, tacking back every 15 minutes or so. We made just 10nm in the first 2 ½ hours. But then, as the water got deeper and we moved away from Lake Michigan’s relatively narrow south end, thing calmed down. The waves subsided as the wind lessened and shifted to the earlier-predicted NE. By the time we got to Waukegan, three hours later, the wind was blowing just 5 knots and from the south. Go figure.

The Lady Elgin

This portion of the lake, Belmont to Waukegan, had been on my personal bucket list for years. I wanted to pay my respects to the wreck that recorded the greatest loss of life on the open waters of the Great Lakes. No, it’s not the Edmund Fitzgerald. She lost 29 when she went down in Lake Superior in a November 1975 storm.

The Lady Elgin, a wooden-hulled, side-wheel steamer, rests at approximately N42 12’, W87 44’ in about 50’ of water. Her wreckage lies in three distinct areas and covers a wide expanse of the bottom just east of Highwood, IL. How she got there in September of 1860 is a story that involves civil war politics, maritime blunders and unselfish bravery.

In 1860, Wisconsin was, as now, a hot-bed of political unrest. Sherman Booth, a Wisconsin abolitionist, editor and politician had created quite a stir when in 1854 he led a raid that freed a runaway Missouri slave from a Milwaukee jail. For the next six years the Wisconsin Supreme Court battled with the U.S. Supreme Court over the proper course of action. The U.S. court held that Booth should be arrested and jailed while the Wisconsin court declared that the Fugitive Slave Law, the support for Booth’s arrest, was unconstitutional. Wisconsin was set to secede from the Union over the matter. Today’s fuss over Wisconsin’s Governor Walker, the “weasel,” seems pretty trite in comparison, huh?

What about the Lady Elgin, you ask?

Wisconsin’s Governor at the time was a Republican and a staunch abolitionist. He polled the various military companies in Wisconsin in an attempt to determine if he had the allies needed if the state were to secede. He found a skunk in the woodpile, in Milwaukee’s Third Ward. Democrat Garrett Barry disagreed with the Governor and in fact, was supporting Stephen Douglas, not Abraham Lincoln, for President. At the time, Barry led the Milwaukee Irish Union Guards, a well respected state-supported militia. In March 1860, the Governor disbanded Barry’s Union Guards.

Garrett Barry wasn’t giving up that easily. He sought and received private donations to re-arm his troops. But the effort fell a little short. By August, he was still in debt about $160. He announced a fundraising excursion to Chicago where those in attendance could both visit the city and hear from their man Stephen Douglas. The trip would take place September 6-7. The Lady Elgin had been chartered.

They made it to Chicago, albeit a little later than planned and without the prospect of hearing from Douglas (he was still in Baltimore and on his way to Harrisburg). By all accounts, however, the roughly 350 Milwaukee residents enjoyed their day in Chicago. By 11 pm on September 7, they were back aboard the Lady Elgin and ready to head back to Milwaukee, roughly 100 miles.

Lee Murdock, the Balladeer of the Great Lakes, tells the rest of the story much better than I ever could.

“A thunderstorm at midnight, big seas began to roll.

One hundred miles of water was the noble steamers goal.

But a fatal slash on her portside from a schooner bearing pine

And an eerie silence shrouded all, the dying engines whined.”

The schooner Augusta disengaged and proceeded on her way to Chicago. She had no way of knowing the damage she had done. Over 300 people lost their lives that night. More than 250 were from Milwaukee, most from the Third Ward. Ninety six survived. It was, and still is, the greatest loss of life on the open waters of the Great Lakes.

There are always goats and heroes in such stories. The Augusta ended her days in shame. Her crews never could escape the dark cloud that hung over the ship. Laws were changed; among them the requirement that sailing vessels carry and use running lights. Light houses were constructed. Plaques were awarded, most notably to Edward Spencer, the Northwestern student who rescued 17 people from the wreck over the course of six hours. His response, when approached by those thanking him was simply, “did I do my best?” We need more Edward Spencer’s!

Waukegan to Milwaukee

We had been in Waukegan harbor in the early 1990s. I have fond memories of that trip including a dinner at Mathon’s and drinks at the Waukegan Yacht Club. Sadly, Jack Benny’s home town is not the same. The harbor docks and boater facilities are new and first rate. Beyond that, there’s not much for the transient boater. Downtown is hard to access and apparently not safe. Many of the building on their main street are now shuttered. The area’s large manufacturing employers are mostly gone leaving the area with high unemployment, disappointment and despair. Evidence that this once was an industrial harbor is all around. Waukegan’s harbor has three Superfund sites of hazardous substances on the National Priorities List.

The city has plans for revitalizing the harbor and lakefront. Most of the industrial activity is to be replaced by residential and recreational space. It’s a huge undertaking. It will take years, perhaps decades, to complete.

Further north, in Wisconsin, the revitalization efforts are further along.

After a weather delay in Waukegan, we headed 16 nm north to Kenosha on Friday July 29th. We had a flat lake and a breeze from the NE that day. We crossed the state line (N42 29.5’) at 9:40 am and were docked at Kenosha’s Southport Marina about an hour later. We were “home” in Wisconsin.

Kenosha (initially Southport), like most of the cities and towns along Lake Michigan’s southwest coast, was settled by immigrant Europeans in the 1830s after the conclusion of the Black Hawk War. In this case, the early settlers came from New York State, looking for a spot on the lakeshore. They settled on the mouth of Pike Creek after failing to find land at either Milwaukee or Racine.

Kenosha and its neighbors to the north, Racine and Milwaukee, were factory towns almost from the start. Wagons, cars, bicycles, farm equipment, etc. were built by the thousands along this coast for about eighty years from roughly 1900-1980. But, unlike Chicago, these cities were left to develop their early harbors without much help from the Federal Government. Despite the obvious financial benefit from the Chicago investment, Democrats in Congress during the late 1830s and 1840s took a strong philosophical view towards limiting the role of the Federal government. A precursor to the Civil War, I suspect. Lincoln, you recall, was a Republican. How times, and political parties, do change!

Much of the manufacturing along this part of the coast, and the jobs that came with it, are now gone. But these are resilient and hard working people. In Kenosha, the lakefront manufacturing plants have been replaced by museums, condominiums, parks, open space and a large, modern marina. Reproductions of the Sheridan LeGrande street lights that were designed for Kenosha by Westinghouse Electric in the late 1920s have been installed on Sixth Avenue. A classic electric street car shuttles residents and tourists from the lakefront to downtown. Festivals and a huge Farmers Market grace the waterfront all summer long.

In Racine, just 9nm north, the redevelopment effort began in the late 1980s. Their waterfront coal piles and oil tanks have been replaced with amenities that cater to the pleasure boater and the tourist. Reefpoint Marina is huge, 900 slips. Spinnakers, a waterfront restaurant and bar, is on-site and typically busy. The walk into the downtown is easy.

Racine’s downtown is dominated by evidence of its primary and long time, employers, S.C. Johnson and J.I. Case. Both have headquarters buildings just a few blocks from the waterfront. S.C. Johnson’s (think household cleaning) HQ building was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Tradition has it that Wright tried to convince the company’s President to build the structure outside the city limits. Wright, it seems, considered Racine to be “backwater.” Hib Johnson disagreed. The building was built downtown but, in a compromise with Wright, it has no windows!

Racine’s other major corporate citizen, Case I H, is also located downtown. Jerome Increase Case was born in Williamstown, NY in 1819. He learned of Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical “reaper” as a young boy. He moved to Wisconsin in 1843 with a plan to build and sell mechanical wheat thrashing machines. The rest, as they say, is history. After many mergers, buy-outs, acquisitions and sell-offs – Tenneco purchased the firm in the 1970s and then sold it again in the late 1990s – the company headquarters remains in Racine. They manufacture tractors in a plant near the city.

Coastal waters near the Racine harbor are a bit of a challenge. More so, perhaps, than any other Lake Michigan port. Racine Reef is just east of the harbor entrance. The reef extends approximately 1.25 nm west to east, is nearly ¾ mile wide and begins about ½ mile from the harbor entrance. While most pleasure boaters would clear the reefs shoal waters, it’s easy to understand the navigational challenges for commercial vessels at this harbor entrance. Then, to the north, there are Wind Point and its North and South shoals. Both are marked with buoys. And, standing guard is the handsome Wind Point light. The light, standing 108 feet tall and visible for a distance of about 15 nm, was first lit in 1880.

Once clear of Wind Point, the skyline of Milwaukee is seen just off the port bow.

What’s not to like about Milwaukee? The harbor is beautiful, accented by the world famous Santiago Calatrava designed Milwaukee Art Museum. The McKinley marina complex, just north of the downtown has everything including the Milwaukee Yacht Club and Veteran’s Park. The docks are in great shape as are the boaters restroom and shower buildings. The complex breakwall structure protects the harbor and McKinley Marina, in particular, from Lake Michigan swells.

In a reoccurring theme, Milwaukee was settled in the 1830s. True enough, Alexis La Framboise (that name again!) established a trading post at the river mouth about 1785 but he was there only in the winter months. It was left to a trio of Solomon Juneau, Byron Kilbourn and George Walker to set the stage for what would become Milwaukee. Each had established competing settlements along the river in the years following 1818. Juneau was apparently the first. We know, for example, that in 1823, he chartered the schooner Chicago Packet to bring trade goods and carry away his furs. Kilbourn, though, was protective of his turf and a protagonist. By the 1840s the rivalry between the towns was quite intense. By design, even the streets of competing towns that terminated at the river didn’t match. In 1840 the Wisconsin Territorial Legislature (Wisconsin didn’t gain statehood until 1848) ignited a fire by ordering that a bridge be built across the river connecting the towns. The Milwaukee Bridge War of 1845 really happened. Bridges were destroyed and people were injured. Eventually, cooler heads prevailed and in 1846 the three communities were united as the City of Milwaukee. Solomon Juneau was the city’s first mayor.

A great deal has changed since then, of course. Milwaukee today is one of America’s great cities. It’s a melting pot with strong and active German, Polish, Italian, Mexican, African American and numerous other transplant nationalities. The city celebrates its diversity with very well attended ethnic festivals on the lakefront all summer long.

The last time we visited Milwaukee by boat (fall 2009), it was Labor Day. Surprisingly, almost nothing in the city was open. We had not been warned. In the summer of 2011, Milwaukee was open for business! Brady Street, just an easy walk west of the marina, was crowded and fun. Downtown was also easy by cab. We rode bikes to the Art Museum. And, to top it off, we took a cab and spent a day at the Wisconsin State Fair. What a hoot. It had been nearly fifty years since either of us had been to Wisconsin’s State Fair (Deb’s last attendance had been when she was three or four, I’m told). Putting icing on the cake, so to speak, we were entertained daily by an air show that routed planes, large and small, over the marina.

_____________________________________________________________________________

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Headed Home

We left Milwaukee on August 8, a Monday, and headed 20 nm north to Port Washington. At 7 am it was overcast but a comfortable 70 degrees. A 5 knot breeze blew from the NW. So, once again, heading NNW, we motor sailed.

Port Washington is a charmer. It’s one of my favorite ports on Lake Michigan. She’s not the same as she once was. Then, none of us is, I suppose. Old Port was a commercial fishing village for most of her history. The Smith Brothers dominated with their fleet of tugs. Their family had been fishing there since 1896. Their restaurant on the waterfront, with its lighted “fisherman with a sturgeon over the shoulder,” logo had attracted patrons from all over the Midwest for years. That all ended in 2006 when, the restaurant, Port Washington’s last fish shanty, closed and was torn down. A fancy new brick building now stands on that strategic place in the harbor. It’s mostly empty.

The commercial fishing boats are also gone now. They’ve been replaced today by pleasure boaters and a handful of charter fishermen. “And now, looking down from St Mary’s, sailboats and freighters are all that pass by…”

For practical purposes, the December 1998 loss of the Linda-E marked the end of commercial fishing in Port Washington. She was a 42’ Smith Brothers tug. She left the harbor on a nice December day. It was sunny and clear. The waters of Lake Michigan were calm. She and her crew of three were never heard from again. Two years later, in 2000, they found her on the bottom, in 250’ of water. After an investigation of the wreck, the Coast Guard concluded that she’d been rammed, most likely by a barge and without notice. She sunk before anyone sounded an alarm. The collision was never reported.

The tourists and boaters still come to Port Washington, as they should. It’s a great town with a very nice marina. The people there try hard to make visiting an enjoyable experience. But when I’m in Port Washington, I think of her past. With St Mary’s church dominating the downtown and her art-deco lighthouse at the harbor entrance, it’s hard not to think of her storied past.

We headed for Sheboygan on August 10. It was sunny with a 10 knot breeze from the NNW. Yes, we were headed north. Sheboygan was to be our last stop on this trip.

Once on the lake we experienced a much stronger NW wind and rough seas. We altered from our normal practice of staying 2 or so nm off shore and headed in to get shelter from Lake Michigan’s bluff. The maneuver worked like a charm. We were secure in Sheboygan by noon.

Sheboygan has a terrific harbor, one of the nicest along Lake Michigan’s west coast. The docks and boater facilities are relatively new. Downtown Sheboygan with its many great restaurants is an easy walk from the marina. The Sheboygan River is lined with shops, restaurants and docks. They’ve preserved several of their once-used fish shanties so the river walk has a historic feel to it. We thoroughly enjoyed the long dinghy trip up the river. My guess is that we’ll do that again.

Sheboygan works hard to accent their maritime history, and even extend it. The Sheboygan Yacht Club has a wonderful clubhouse and marina (rare for Lake Michigan, we’ve found). The club is an active citizen on the waterfront. Sheboygan is also home to Sail Sheboygan, an organization founded in 2004 to promote national and international sailing competitions in the harbor. In September 2011, for example, they hosted the Nations Cup, a competition involving sailors from 20 different countries.

Just a few miles north of the harbor entrance, one finds the internationally acclaimed Whistling Straits golf complex. Whistling Straits is one of two Kohler golf properties, and four courses, in the area; the other being Black Wolf Run, and home of PGA Championships and other international golf competitions. From the water one can easily distinguish the roughly two miles of coastline occupied by the Straits golf course. It’s a view only the boaters get. I’m not a golfer but this is a beautiful site.

We left Sheboygan on Friday August 12. It was a beautiful day with sunny skies and a 10 knot breeze from the SW. On our last day of the trip, we would not have to fight the wind. We hoisted the jib and slid home with a following sea. We were secure in our Manitowoc Marina slip by noon.

Concluding Thoughts

Visits to these busy and populated ports today complicate an understanding of their past. The pine forests are gone as are the fur bearing beaver, mink and otter. The river entrances have all been “improved” by huge man made breakwall systems. There’s even a lock in Chicago to manage the flow of Lake Michigan’s water out and into the Chicago River. The “manufacturing age” has disfigured the harbors on Lake Michigan’s south and southwest end but each, at its own pace, is making a comeback. And, particularly on the Michigan side, so are the forests. The schooners are gone, of course but huge freighters still transport finished goods and natural resources to and from population centers on the lake. Christmas trees still come to the Chicago harbor even though the Rouse Simmons rests on the bottom in 250’ of water ENE of Two Rivers, WI. Today, the Coast Guard makes that ceremonial delivery.

With a little effort, though, and a watchful eye, it’s still possible to feel the past and hope for the future. For me, the harbor entrance lights and the towers along the way help a great deal. They demonstrate the never ending need for guiding lights both literally and figuratively. GPS be damned, I’m always on the lookout for guiding lights, whether on the water or not..

Lake Michigan remains largely the same. She is still beautiful, big and sometimes dangerous. She’s unpredictable. The fact that WingNuts was of an “unsuitable, unconventional design” does not make her unique in explaining the loss of life on Lake Michigan. The Griffon never made it back to eastern Lake Erie. The Hercules never made it to Detroit with her load of whiskey. The Eastland never made it out of the Chicago River on that warm and sunny summer day. The Lady Elgin left a mark on Milwaukee’s early history because she failed to finish her trip on that stormy night just north of Chicago. We have no way of knowing how many others “failed to reach the shore” or what their contribution might have been. We’re left to cover for their loss. Some would say that all of mans inventions, particularly those designed to "conquer" the planet, have proven to be “unsuitable” in the face of Mother Nature’s fury.

These Great Lakes teach humility. At least they should.

Despite her dangerous side, this beautiful lake continues to serve. She was a better alternative than the overland routes for the Native Americans and then for the European immigrants who settled here in the 1800s. That’s still the case today, particularly for things like coal, iron ore, calcite and cement. I never tire of watching the big freighters ply these waters. She supplies clean drinking water for those who live along her shores as she has done for thousands of years. And, she is a play land, as she always has been. The number of people she serves has increased dramatically over the years but her role remains a constant. She is uplifting and, like life, different every single day.

“But no words can compare with the spray in the air

The wind in the rigging, the rush of the tide

The song of the sea can only be heard

By casting your cares to the water”